BRUCH: Kol Nidrei -- Adagio on Hebrew melodies, Op. 47

János Starker, cello; London Symphony Orchestra, Antal Dorati, cond. Mercury, recorded in Watford Town Hall, London, July 10, 1962

FAURÉ: Élégie in C minor, Op. 24

János Starker, cello; Philharmonia Orchestra, Walter Susskind, cond. EMI, recorded in Kingsway Hall, London, July 16-17, 1956

by Ken

I've been trying like heck to finish up our Boston Symphony new-concertmaster series, eapecially now that the new incumbent, Nathan Cole, is officially on the job. I've made grinding but steady(ish) progress but still haven't gotten there. I might make casual mention of certain, oh, medical issues, possibly involving picturesque words like "major" and "surgery" and "this week," but that would fall ignobly under the heading of dime-store alibi-ing.

Anyway, I decided, as you'll have noticed, that we'd join The Strad, which has been publishing and republishing encomia on a daily basis, in remembrance of the great, protean cellisst János Starker, on -- or slightly after -- what would have been his 100th birthday, and we'll do it by dipping into the predictably Starker-rich SC Archive. We've led off with the two great cello-and-orchestra elegies. We can lighten the mood by selecting carefully in the musical set for which Starker was probably most famous, the six Bach cello suites. We'll go with the C major Suite, No. 3.

Showing posts with label Josef Suk. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Josef Suk. Show all posts

Monday, July 8, 2024

Remembering János Starker

on (OK, slightly after) his 100th

János Starker (July 5, 1924 — Apr. 28, 2013)

Sunday, June 30, 2024

45 seconds' worth of music

I can't get out of my head

We've heard it before (and we're going to hear it again)

Technically, it's not really even part of a movement of the Mendelssohn E minor Violin Concerto, these 14 bars of Allegretto non tanto which provide a transitional bridge from the sublime central Andante to the romping rondo (as announced in the Allegro molto vivace above). I'm used to having the Andante seize control of me -- but this little Allegretto non troppo?

by Ken

Okay, I admit I was having a little fun with the part about our having "a soloist and conductor so closely in sync," but I wasn't kidding about "the conductor [having] the orchestra not just phrasing but practically breathing with the soloist."

LAST WEEK WE HEARD IT TACKED ONTO THE ANDANTE

ii. Andante -- Allegretto non tanto

Utah Symphony Orchestra, Joseph Silverstein, violin and cond. Pro Arte, recorded in Symphony Hall, Salt Lake City, Nov. 19 & 21, 1983

And I wrote this about it:

AND LET IT RUN THROUGH TO THE END OF THE RONDO

end of ii. Andante -- Allegretto non troppo [at 1:05] --

iii. Allegro molto vivace [at 1:51]

Joseph Silverstein, violin, with the Utah Symphony (credits as above)

WE'VE ACTUALLY HEARD A BUNCH OF PERFORMANCES

OF THE ANDANTE OF THE MENDELSSOHN CONCERTO

And in a number of cases I stopped the clip at the end of what I would call "the Andante proper." No reason for this than I can recall -- I think it just hadn't occurred to me to be sure to tack on the Allegretto non tanto. Very possibly I was thinking that such a hanging-in-mid-air ending would be bad form for our listening experience, and only later came to realize that this very up-in-the-airness teaches us a lesson about the structure of the concerto.

Technically, it's not really even part of a movement of the Mendelssohn E minor Violin Concerto, these 14 bars of Allegretto non tanto which provide a transitional bridge from the sublime central Andante to the romping rondo (as announced in the Allegro molto vivace above). I'm used to having the Andante seize control of me -- but this little Allegretto non troppo?

by Ken

Okay, I admit I was having a little fun with the part about our having "a soloist and conductor so closely in sync," but I wasn't kidding about "the conductor [having] the orchestra not just phrasing but practically breathing with the soloist."

LAST WEEK WE HEARD IT TACKED ONTO THE ANDANTE

ii. Andante -- Allegretto non tanto

Utah Symphony Orchestra, Joseph Silverstein, violin and cond. Pro Arte, recorded in Symphony Hall, Salt Lake City, Nov. 19 & 21, 1983

And I wrote this about it:

"No, don't crank up the volume at the start! Our soloist is really choosing to play this music -- which I sometimes think just may be the most beautiful ever written -- so, er, confidentially. There's plenty of presence in the sound; I'd describe it as quite intense; the soloist just isn't going to make a display of it. Meanwhile the conductor has the orchestra not just phrasing but practically breathing with the soloist. How often do you get a soloist and conductor so closely in sync?"NOW LET'S BACK UP A BIT -- INTO THE ANDANTE --

AND LET IT RUN THROUGH TO THE END OF THE RONDO

end of ii. Andante -- Allegretto non troppo [at 1:05] --

iii. Allegro molto vivace [at 1:51]

Joseph Silverstein, violin, with the Utah Symphony (credits as above)

WE'VE ACTUALLY HEARD A BUNCH OF PERFORMANCES

OF THE ANDANTE OF THE MENDELSSOHN CONCERTO

And in a number of cases I stopped the clip at the end of what I would call "the Andante proper." No reason for this than I can recall -- I think it just hadn't occurred to me to be sure to tack on the Allegretto non tanto. Very possibly I was thinking that such a hanging-in-mid-air ending would be bad form for our listening experience, and only later came to realize that this very up-in-the-airness teaches us a lesson about the structure of the concerto.

Monday, January 3, 2022

We now hear our "elite" violin concertos in their entirety

As we edge forward with our Mendelssohn "sidebar" -- as I just explained -- it's time to hear these concertos in full.

AGAIN, WE REALLY HAVE TO START WITH MOZART

In our original consideration of the place of the rondo finale in the line of the great violin concertos, we started with Mozart --

• not because he invented either the violin concerto or the rondo or even the use of the rondo in violin (and other) concertos, which he didn't, but because he grasped the possibilities of this combination in a way, or ways, that made it stick.

• and not because Mozart's violin concertos, taken on their own, are equivalent in stature to the line of violin concertos they did so much to inspire. The form -- the Classical concerto, that is, not to be confused with the Baroque one -- was still too new to aspire to that stature. (Thank you once again, Herr Beethoven.)

Not that the three "mature" concertos (which followed with scarcely any separation from the not-yet-mature ones) can't still hold their own on a concert platform. But you kind of feel that the audience needs at minimum a somewhat bigger kick, and the performer has to put out a portion more to earn his/her fee. So, with no disrespect to any of these much-loved works, I'm thinking of them maybe more as a collective than as separate entires in our violin-concerto sweepstakes. (If it were piano concertos we were tracking, I'm not sure I would take the same position. But Mozart's piano concertos come from a more developed stage of his creative energies. There are at least half a dozen Mozart piano concertos I'd consider worthy of inclusion in such a survey.

BUT: We're skipping the Mozart Violin Concertos Nos. 1-2

[TUESDAY UPDATE: You might watch for updates to this post, like the one I just added for the Brahms Concerto.]

Last week ("Rondomania: A quick hit at violin-concerto rondo finales looking back from Mendelssohn to Mozart and Beethoven and ahead to Brahms and Sibelius"), pursuing the Mendelssohn "sidebar" that grew out of the Nov. 28 post "One Sunday afternoon in

August 1943 in Carnegie Hall . . .," we listened to the great chain of violin concertos with rondo finales stretching out before and after Mendelssohn. I said at the time that I'd really like to be able to present those concertos in full. Well, here they are!

This all still needs to be integrated with a mostly written first part that continues the Mendelssohnian thread. And probably it should be improved in all sorts of other ways. I wouldn't hold my breath about that part, though. -- Ken

AGAIN, WE REALLY HAVE TO START WITH MOZART

In our original consideration of the place of the rondo finale in the line of the great violin concertos, we started with Mozart --

• not because he invented either the violin concerto or the rondo or even the use of the rondo in violin (and other) concertos, which he didn't, but because he grasped the possibilities of this combination in a way, or ways, that made it stick.

• and not because Mozart's violin concertos, taken on their own, are equivalent in stature to the line of violin concertos they did so much to inspire. The form -- the Classical concerto, that is, not to be confused with the Baroque one -- was still too new to aspire to that stature. (Thank you once again, Herr Beethoven.)

Not that the three "mature" concertos (which followed with scarcely any separation from the not-yet-mature ones) can't still hold their own on a concert platform. But you kind of feel that the audience needs at minimum a somewhat bigger kick, and the performer has to put out a portion more to earn his/her fee. So, with no disrespect to any of these much-loved works, I'm thinking of them maybe more as a collective than as separate entires in our violin-concerto sweepstakes. (If it were piano concertos we were tracking, I'm not sure I would take the same position. But Mozart's piano concertos come from a more developed stage of his creative energies. There are at least half a dozen Mozart piano concertos I'd consider worthy of inclusion in such a survey.

BUT: We're skipping the Mozart Violin Concertos Nos. 1-2

Labels:

Beethoven,

Brahms,

David Oistrakh,

Dvorak,

Isaac Stern,

Jascha Heifetz,

Josef Suk,

Joseph Szigeti,

Mendelssohn,

Mozart,

Nathan Milstein,

Sibelius,

Tchaikovsky,

Violin Concerto,

Yehudi Menuhin

Monday, September 6, 2021

What we've wound up with: (1) We inch our way back toward Dvořák's New World Symphony, and (2) We explore the problem of stuff going missing, G&S-style*

*Technically this should be "B&S-style," I know, but there's no such thing, is there? -- Ed.

UPDATE: I GIVE UP! THOSE CDs I NEEDED, WHICH I HAD LYING

ABOUT OR IN MY HAND, ARE MIA -- LET'S JUST GET ON WITH IT

(No "Schubert piano performance that knocked me over," for now)

When, in 1997, this statue of Dvořák by the Croatian-American sculptor Ivan Meštrović found a new home near the northern edge of Manhattan's Stuyvesant Square, it constituted a "homecoming" of sorts. There's a story here, and a personal story, er, inside the story which involves a remarkable walking tour and two remarkable musicians who both have powerful connections -- of very different sorts -- to the great Czech composer.

DVOŘÁK: Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53:

iii. Finale: Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo

Josef Suk, violin; Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Karel Ančerl, cond. Supraphon, recorded in the Rudolfinum, Prague, August 1960

DVOŘÁK: Piano Trio No. 4 in E minor, Op. 90 (Dumky):

the first two of the trio's six movements --

i. Lento maestoso -- Allegro quasi doppio movimento -- Lento maestoso (Tempo I) -- Allegro

ii. Poco adagio -- Vivace non troppo -- Poco adagio -- Vivace

[ii. at 4:04] Suk Trio: Josef Suk, violin; Josef Chuchro, cello; Jan Panenka, piano. Supraphon-Denon, recorded in the Domovina Studio, Prague, May 11-13, 1978

DVOŘÁK: Symphony No. 8 in G, Op. 88:

i. Allegro con brio

New York Philharmonic, Kurt Masur, cond. Teldec, recorded live in Avery Fisher Hall, Jan. 1-4, 1993

DVOŘÁK: Slavonic Dance No. 15 in C, Op. 72, No. 7

Gewandhaus Orchestra (Leipzig), Kurt Masur, cond. Philips-Deutsche Schallplatten, recorded 1984-85

by Ken

Nothing continues to come together right, but we forge ahead, with one qualification: Tomorrow I'm going to the Richmond County Fair, come hell or high waters. On second thought, we best not kid around about "high waters, of which we Gothamites had a plentiful share this week. In fact, I'm going to have to check the website to make sure the fair is up and running -- they were supposed to open yesterday, which would have been quite a feat so soon after the deluge.

Anyway, that's my nonnegotiable schedule delimiter, and it remains to be seen how far further I can get tonight, especially with multiple CDs going missing on me. Meanwhile, these audio clips are ready to roll, so why don't we let them? (For the record, as it were, three of the four clips so far in place are Sunday Classics premieres, I think -- I did find an older version of one of the three in the Archive.)

FOR NOW, WE CAN AT LEAST HAVE THE STORY

OF THE STATUE THAT "FOUND ITS WAY HOME"

UPDATE: I GIVE UP! THOSE CDs I NEEDED, WHICH I HAD LYING

ABOUT OR IN MY HAND, ARE MIA -- LET'S JUST GET ON WITH IT

(No "Schubert piano performance that knocked me over," for now)

When, in 1997, this statue of Dvořák by the Croatian-American sculptor Ivan Meštrović found a new home near the northern edge of Manhattan's Stuyvesant Square, it constituted a "homecoming" of sorts. There's a story here, and a personal story, er, inside the story which involves a remarkable walking tour and two remarkable musicians who both have powerful connections -- of very different sorts -- to the great Czech composer.

DVOŘÁK: Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53:

iii. Finale: Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo

Josef Suk, violin; Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Karel Ančerl, cond. Supraphon, recorded in the Rudolfinum, Prague, August 1960

DVOŘÁK: Piano Trio No. 4 in E minor, Op. 90 (Dumky):

the first two of the trio's six movements --

i. Lento maestoso -- Allegro quasi doppio movimento -- Lento maestoso (Tempo I) -- Allegro

ii. Poco adagio -- Vivace non troppo -- Poco adagio -- Vivace

[ii. at 4:04] Suk Trio: Josef Suk, violin; Josef Chuchro, cello; Jan Panenka, piano. Supraphon-Denon, recorded in the Domovina Studio, Prague, May 11-13, 1978

DVOŘÁK: Symphony No. 8 in G, Op. 88:

i. Allegro con brio

New York Philharmonic, Kurt Masur, cond. Teldec, recorded live in Avery Fisher Hall, Jan. 1-4, 1993

DVOŘÁK: Slavonic Dance No. 15 in C, Op. 72, No. 7

Gewandhaus Orchestra (Leipzig), Kurt Masur, cond. Philips-Deutsche Schallplatten, recorded 1984-85

by Ken

Nothing continues to come together right, but we forge ahead, with one qualification: Tomorrow I'm going to the Richmond County Fair, come hell or high waters. On second thought, we best not kid around about "high waters, of which we Gothamites had a plentiful share this week. In fact, I'm going to have to check the website to make sure the fair is up and running -- they were supposed to open yesterday, which would have been quite a feat so soon after the deluge.

Anyway, that's my nonnegotiable schedule delimiter, and it remains to be seen how far further I can get tonight, especially with multiple CDs going missing on me. Meanwhile, these audio clips are ready to roll, so why don't we let them? (For the record, as it were, three of the four clips so far in place are Sunday Classics premieres, I think -- I did find an older version of one of the three in the Archive.)

FOR NOW, WE CAN AT LEAST HAVE THE STORY

OF THE STATUE THAT "FOUND ITS WAY HOME"

Monday, August 9, 2021

You might still catch the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center's Schubert Quintet before 7:30pm tonight (Aug. 9). But if not --

Violinists Arnaud Sussmann and Paul Huang, cellists David Finckel and Nicholas Canellakis, and violist Matthew Lipman performed the sublime Schubert String Quintet in C in the "Evenings at the Frederick R. Koch Foundation Townhouse" concert streamed free on the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center website for a week beginning last Monday (August 2), and theoretically available until 7:30 tonight, when --

Violinists Arnaud Sussmann and Paul Huang, cellists David Finckel and Nicholas Canellakis, and violist Matthew Lipman performed the sublime Schubert String Quintet in C in the "Evenings at the Frederick R. Koch Foundation Townhouse" concert streamed free on the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center website for a week beginning last Monday (August 2), and theoretically available until 7:30 tonight, when --This week's program streams live --

with Paul Huang and Nicholas Canellakis returning, joined by violinist Sean Lee and violists Misha Amory and Hsin-Yun Huang, for (as I described it recently) Dvořák's "strange and surprising and also singularly luscious" Terzetto for two violins and viola, Op. 74 (which we listened to in the June 6 post, "At the very least, we can listen to this vaguely weird and utterly beguiling little Dvořák piece"), and Mendelssohn's added-viola Second String Quintet. Still to come: on August 16, Ravel's Violin Sonata and Rachmaninoff's Cello Sonata; from August 23, "Schubert Fantasies" (the great F minor for piano four hands, D. 940 and the C major for violin and piano, D. 934); and on August 23, the First Piano Trios of Beethoven and Saint-Saëns played by pianist Anne-Marie McDermott, violinist Chad Hoopes, and cellist Dmitri Atapine.

General tip: Keep an eye on the CMS website's "Watch & Listen" page to see what's currently available and coming up.

by Ken

Call it simple dereliction of duty, on account of that's what it is. When I got the idea for this stopgap post, stalling for time while I try to make one of the dozen or so stalled posts materialize, you would have had a good day, or maybe two, to catch the Chamber Music Society of Lincolin Center's offering of the above-referenced concert performance of the one-of-a-kind Schubert String Quintet. By now, alas, unless you've super-quickly found this post with enough time to spare, it's too late, since at 7:30 tonight (August 9) the next program in CMS's Evenings at the Frederick R. Koch Foundation Townhouse series takes over the slot, with two more programs to follow, starting August 16 and 23.

Assuming you've mised the CMS Schubert Quintet, and have finished venting (altogether appropriate under the circumstances), in partial compensation -- or even if you managed to squeeze it in -- here's a taste in the form of what may be the single most beautiful movement of music ever concocted.

SCHUBERT: String Quintet in C, D. 956:

ii. Adagio

Josef Suk and Jiří Baxa, violins; Ladislav Černý, viola; Saša Večtomov and Josef Simandl, cellos. Praga, recorded live in Dvořák Hall in the Rudolfinum, Prague, Jan. 31, 1971

Melos Quartet Stuttgart (Wilhelm Melcher and Gerhard Voss, violins; Hermann Voss, viola; Peter Buck, cello); Mstislav Rostropovich, cello. DG, recorded 1977

(If you're still feeling cheated, I can reveal that we're going to hear the whole of the quintet, in an interesting assortment of performances, including the entirety of the two we've just sampled. I hope you noticed, in the 1971 Prague performance, the special glow of the Adagio's gorgeous violin solos. It's worth remembering that the first violinist here, Josef Suk, one of the 20th century's great violinists, was also a compulsive chamber-music player, who from 1951 on pretty much always found time in his concert and recording schedules to accommodate a standing piano trio. Cellist Saša Večtomov, by the way, was a member of that inaugural 1951 Suk Trio.)

YOU'RE PROBABLY WONDERING WHAT THE PLAN IS

(OR WHETHER THERE'S ANY KIND OF PLAN AT ALL)

Sunday, May 31, 2020

Can we talk? Or maybe for now mostly listen? (Coming up we've got Beethoven and Elgar, both worth hearing!)

BEETHOVEN: Piano Trio No. 1 in E-flat, Op. 1, No. 1:

i. Allegro

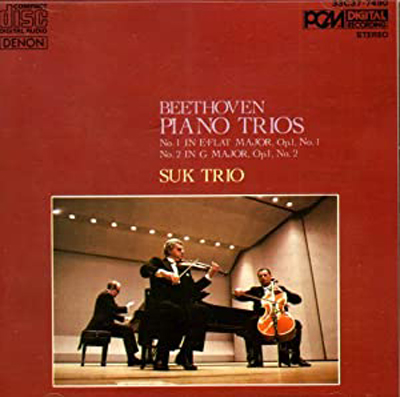

Suk Trio (Josef Suk, violin; Josef Chuchro, cello; Josef Hála, piano). Denon-Supraphon, recorded in Prague, December 1983

by Ken

Sometimes the eerie solitude of this space has its advantages. It is, notably, a not-so-bad place to come to be alone. And after the exhaustive purposelessness of last week's remembrance of bass John Macurdy, I have a couple of quasi-self-therapeutic goals to attempt, starting with this presentation of the opening movements of the first two of the three piano trios that make up Beethoven's Op. 1. I spent what is for me a lot of money to acquire this CD, one of two I was missing from the series of "complete" Beethoven piano trios ("complete" in quotes because of the numerous questions that come into play when we try to define what constitutes "all" of Beethoven's works for piano trios) as recorded by the Suk Trio as constituted above in the early 1980s, the dawn of the digital era, as coproduced by the Japanese and Czechoslovak companies Denon and Supraphon.

For reasons I can't begin to understand, these CDs have been out of print for ages, and the prices of used copies of some of them have risen to weird levels. Over the years I have periodically gone to the shelf to: (a) figure out which CD or CDs exactly I was missing and (b) reconnoitre online to see what it would cost to complete my holdings. Each time I eventually figured out that I was missing the CDs that contain what we traditionally think of as "the first four" Beethoven piano trios: the three trios of Op. 1 and the Op. 11 Trio, written for clarinet rather than violin but playable either way. Some of you may recall that one of the many Sunday Classics threads currently suspended in mid-air is some consideration of this very trio, Op. 11, alongside Mozart's sublime Clarinet Quintet. This may have been the proximate cause of my most recent reinvestigation of the Suk Trio Beethoven lacunae.

THE DECISION I MADE . . .

Labels:

Beethoven,

Chilingirian Quartet,

Elgar,

Jan Panenka,

Josef Chuchro,

Josef Hala,

Josef Suk,

Nash Ensemble,

Op. 1 No. 3,

Op. 11,

Piano Quintet,

Piano Trio,

Schubert Ensemble of London,

Suk Trio

Sunday, April 14, 2013

From brooding depths to sparkling heights -- Bruch's G minor Violin Concerto

Itzhak Perlman plays the opening Prelude (Allegro moderato) of the Bruch G minor Violin Concerto, with Kazuyoshi Akiyama conducting the Tokyo Symphony Orchestra.

by Ken

In Friday night's "Max Bruch preview" we heard the composer's Kol Nidrei, an "Adagio based on a Hebrew melody," which I described as his second-best-known work. "The best-known," I wrote, "surely is his G minor Violin Concerto," noting that we would be listening to it today.

An obvious point of reference for what used to be known as "the Bruch Violin Concerto" but now has to be called "the Bruch First Violin Concerto" because there are two more (both craftsmanlike works but neither with anything like the irresistible appeal of the first), is the Sibelius D minor Violin Concerto, which is also through much of its way darkly brooding, then bursts out into a more animated finale. The Sibelius Concerto, though (which we heard in the November 2009 post "An intrepid voice from the rugged North -- Jan Sibelius"), was written 35-plus years later.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)