BEETHOVEN: Piano Trio No. 1 in E-flat, Op. 1, No. 1:

i. Allegro

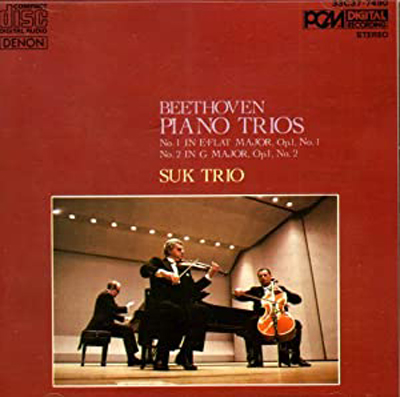

Suk Trio (Josef Suk, violin; Josef Chuchro, cello; Josef Hála, piano). Denon-Supraphon, recorded in Prague, December 1983

by Ken

Sometimes the eerie solitude of this space has its advantages. It is, notably, a not-so-bad place to come to be alone. And after the exhaustive purposelessness of last week's remembrance of bass John Macurdy, I have a couple of quasi-self-therapeutic goals to attempt, starting with this presentation of the opening movements of the first two of the three piano trios that make up Beethoven's Op. 1. I spent what is for me a lot of money to acquire this CD, one of two I was missing from the series of "complete" Beethoven piano trios ("complete" in quotes because of the numerous questions that come into play when we try to define what constitutes "all" of Beethoven's works for piano trios) as recorded by the Suk Trio as constituted above in the early 1980s, the dawn of the digital era, as coproduced by the Japanese and Czechoslovak companies Denon and Supraphon.

For reasons I can't begin to understand, these CDs have been out of print for ages, and the prices of used copies of some of them have risen to weird levels. Over the years I have periodically gone to the shelf to: (a) figure out which CD or CDs exactly I was missing and (b) reconnoitre online to see what it would cost to complete my holdings. Each time I eventually figured out that I was missing the CDs that contain what we traditionally think of as "the first four" Beethoven piano trios: the three trios of Op. 1 and the Op. 11 Trio, written for clarinet rather than violin but playable either way. Some of you may recall that one of the many Sunday Classics threads currently suspended in mid-air is some consideration of this very trio, Op. 11, alongside Mozart's sublime Clarinet Quintet. This may have been the proximate cause of my most recent reinvestigation of the Suk Trio Beethoven lacunae.

THE DECISION I MADE . . .

. . . was to sort of split the difference: pull the trigger on the first Suk Beethoven CD, which cost more than I would normally spend for such a thing, but not nearly as much as the second CD, regarding which I would postpone a decision until, well, some other time. As you can hear (from above and below), the strategy has succeeded up to a point, that point being disc of Op. 1, Nos. 1 and 2, arrived from Japan -- pretty quickly, as it happens. Too soon, indeed, to enable me to comfortably reopen the question of the second, larger expenditure for the now-identified single missing CD. Which has left me stranded in this odd world of Beethoven-in-the-world-of-Haydn.

BEETHOVEN: Piano Trio No. 2 in G, Op. 1, No. 2:

i. Adagio; Allegro vivace

Suk Trio (Josef Suk, violin; Josef Chuchro, cello; Josef Hála, piano). Denon-Supraphon, recorded in Prague, April 1984

Like Op. 1, No. 1, Op. 1, No. 2 is an utterly gorgeous piece. (Note Beethoven playing with the stratagem of starting a "sonata form" opening movement with a slow introduction -- something he would continue to do when he judged the time right, to wonderful effect, just as both Haydn and Mozart had done.) And I should have been quicker to say that there's anything wrong with being in the world of Haydn -- provided you're Haydn. If you're Haydn, this is a splendid place to be, through all the evolutions and transformations it had undergone over that master's long and singularly productive creative span.

The problem comes if you're not Haydn but Beethoven, working at figuring out who you are, musically, and who you want to be. And there wasn't any problem through those first two piano trios. This is a medium, we should recall, that Haydn himself was enormously fond of, though it doesn't seem ever to have occurred to him to use it in more dramatic ways, as he had been doing in all sorts of ways in his string quartets and symphonies, not to mention the overtly dramatic late oratorios, The Creation and The Seasons. And even as Beethoven played with the piano trio form, and won approval and encouragement for the first two works he produced in this set, he clearly knew he had boundaries to break through. Did it occur to him that Haydn would think he'd gone nuts? Well, he did.

BEETHOVEN: Piano Trio No. 3 in C minor, Op. 1, No. 3:

i. Allegro con brio

[no exposition repeat] Hungarian Trio (Arpad Gérecz, violin; Vilmos Palotai, cello; Georges Solchany, piano). EMI, recorded in Paris, c1959

Stern-Rose-Istomin Trio (Isaac Stern, violin; Leonard Rose, cello; Eugene Istomin, piano). CBS-Sony, recorded in New York City, Nov. 3, 1966

For Beethoven there was no going back. He still had a lot to discover about himself musically, and a lot of ways and directions in which to grow, but he had taken a necessary step, and in the process likely developed a degree of trust in his instincts and where they would lead him.

While we're at it, we really ought to hear the rest of Op. 1, No. 3, no? It's laid out -- like Nos. 1 and 2, for that matter -- in what looks like perfectly standard four-movement form: a sonata-form allegro, a slow movement, a scherzo (Nos. 1-2) or minuet (No. 3), and a quick-tempo finale. Except that, this being Beethoven's Op. 1, he's deciding what at least for now is going to be his "standard" form. And note that it's not by outward form that No. 3 takes its leap beyond Nos. 1 and 2; in fact, it takes what we might call a step backwards, retaining the old-school minuet rather than the newer-fangled scherzo.

ii. Andante cantabile con variazioni

Jaime Laredo, violin; Sharon Robinson, cello; Joseph Kalichstein, piano. Koch International Classics, recorded, um, ya-got-me

iii. Menuetto: Quasi allegro

Itzhak Perlman, violin; Lynn Harrell, cello; Vladimir Ashkenazy, piano. EMI, recorded in London, early 1980s

iv. Finale: Prestissimo

Hungarian Trio (Arpad Gérecz, violin; Vilmos Palotai, cello; Georges Solchany, piano). EMI, recorded in Paris, c1959

One thing I notice about my own intake of the Beethoven Op. 1 trios is how satisfyingly the three works complement one another. As much as I love Nos. 1 and 2, without No. 3 they seem incomplete.

And again, as long as we're here, it's worth at least noting that, after the breakthrough of Op. 1, No. 3, Beethoven didn't find occasion to take up the piano trio seriously again until the two trios of Op. 70! But what, you ask, about Op. 11, that curious hybridized piano trio with either clarinet or violin taking its upper non-piano voice? Again, this is a work we still have some further playing-with up ahead. It does seem a special case, though, with its featured clarinet part, and in addition it does seem clearly a step back in terms of artistic ambition from Op. 1, No. 3. That said, it's by no means a trivial or dashed-off piece. Let's listen to its central Adagio, in both its guises, with clarinet and violin. This may not be Beethoven's most elaborate slow movement but nevertheless has an emotional breadth and even amplitude that mark it for me as indelibly "Beethovenian."

BEETHOVEN: Piano Trio No. 4 in B-flat, Op. 11:

ii. Adagio

With clarinet: Richard Stoltzman, clarinet; Alain Meunier, cello; Rudolf Serkin, piano. Marlboro Recording Society-CBS-Sony, recorded at Marlboro (Vermont), July 21, 1974

With violin: Stern-Rose-Istomin Trio (Isaac Stern, violin; Leonard Rose, cello; Eugene Istomin, piano). CBS-Sony, recorded in New York City, July 11, 1969

WHICH BRINGS ME TO MY PERSONAL QUESTION:

DO I NEED THAT STILL-MISSING SUK TRIO CD?

I did find the Suk Trio performance of Op. 11 (with Josef Suk playing the violin part; no clarinet), and liked it well enough. I'm not exactly wanting for performances of either work -- on LP, CD, and even open-reel, so do I really need the missing CD? In particular, at a time when it seems like kind of a crazy expenditure.

In other words, is my aching desire for it less a matter of musical craving than compulsive completeness? I'm aware that this compulsiveness has driven a certain part of my record-collecting, and I'm also aware that, as many records as I have, this mania has the effect of making the records I don't have feel more important than all the ones I do have.

I don't have an answer. I'm thinking, though, that putting the question out there in this theoretically public place may have the effect of keeping the madness in check.

And it so happens that I do have a Suk Trio recording of Op. 1, No. 3 -- an earlier one, made when Suk's trio partner, along with cellist Josef Chuchro, was other longest-term trio-mate, pianist Jan Panenka. In fact, my first exposure to the Suk Trio was in its longtime Suk-Chuchro-Panenka configuration. In the mid-'60s this version of the Suk Trio made beautiful stereo recordings for Supraphon of a coupling of Op. 1, No. 3 and of Op. 70, No. 1, the Ghosts Trio; and of the grandest and greatest of the Beethoven piano trios, one of the supreme chamber works, the Archduke Trio, Op. 97. Those were among a number of Supraphon LPs licensed for domestic issue on the Crossroads budget line of CBS's Epic label, and what a treasure they were! So if I want to hear the Suk Trio play Op. 1, No. 3 I can -- and one of these days I really ought to relisten to both of those LPs.

At a time when my wandering ruminations take me to all sorts of places I wasn't expecting, I experienced a momentary twinge that the digital Suk Trio Beethoven recordings were without Panenka (so closely connected in my mind with his trio-mates in part because he partnered both Suk and Chuchro in their recordings, which I love, of the complete Beethoven sonatas for their instruments). This is just a memory lapse, because it was in 1979 that Panenka became yet another in a long line of pianists who find themselves with a damaged hand. (I haven't researched this, but I assume it was, as it usually is, the right hand. Considering what concert pianists ask their poor right hands to do, it's amazing that any of them retain complete use of theirs.) And so, giving way to practical necessity, his place was taken in the trio by another fine pianist, Josef Hála.

I gather that Panenka did eventually resume playing, and according to a stub article in Wikipedia he was the pianist of the Suk Trio's final performances, in 1990. But at a time when lines of fortune, and their twists and turns, are much on my mind, I found myself face-to-face with another one.

All the more reason why I should listen to those Beethoven trio performances with Panenka. I still won't be able to share them with you, though, since I still can't replace the stylus of the phono cartridge on my digitizing turntable, and while I've got severeal perfectly usable phono cartridges lying dormant, the cartridge in this tone arm doesn't seem to be replaceable.

QUASI-THERAPEUTIC ISSUE NO. 2:

HOW EFFECTIVE IS THERAPY-BY-PIANO-QUINTET?

This is really an entirely different sort of question, but it concerns another issue I've been trying to deal with in this space. It concerns a work, the Elgar Piano Quintet of 1918, whose opening movement I began picking at well over a year ago after finding myself powerfully moved by it, at a fairly iffy time for me, in a really fine concert by the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. A good part of the problem was that the first few performances I tracked down in my post-concert investigations seemed to me an almost total bust, to the point of making me wonder what the musicians thought was happening -- while as far as I could hear nothing was happening.

The Piano Quintet came into being in a year that began as the worst in Elgar's life, a time when everything in his life had pretty much collapsed and left him in something like total despair. The unyielding madness of the years of war had poisoned if not actually destroyed an enormous part of what he thought of as human civilization; his own physical health, was debilitatingly awful; and -- no doubt part and parcel of the above -- what his creative impulses had shut down completely.

The Piano Quintet, which I really hadn't known before it presented itself so unexpectedly in my life, seems clearly bound up in both Elgar's despair and his miraculous emergence from it. In intriguingly overlapping ways, a Violin Sonata and a String Quartet were created in the same period that produced the Piano Quintet, and the ground was laid for what many Elgar enthusiasts consider perhaps his most personal creation, the Cello Concerto.

I have to say that none of my efforts to "crack" those three other works have yielded much result. But the Piano Quintet, that's a different story. I still can't talk coherently about any of this. But it's struck me as I've nosed around the quintet that its second and third movements are maybe the most beautiful music of Elgar's I know, clearly inspired by the West Sussex countryside around Brinkwells the home where he weathered the worst of his crisis, cared for by Lady Elgar, and underscore the reality that the Piano Quintet couldn't have been written if the composer hadn't managed some sort of core reconstruction of his shattered reality. So I thought we might try, as an experiment, working somewhat backwards, listening first to the second and third movements, and then going back to the first movement, where it still seems to me that Elgar's personal battle for survival, both his own and the world's, was fought.

Clearly the proper effect of the later movements depends on hearing them in their proper order. Nothing stops us, however, from returning to them after taking in the first movement.

ELGAR: Piano Quintet in A minor, Op. 84:

ii. Adagio

Nash Ensemble (Ian Brown, piano; Marcia Crayford and Elizabeth Layton, violins; Roger Chase, viola; Christopher van Kampen, cello). Hyperion, recorded in London, Dec. 8-10, 1992

iii. Andante; Allegro

Schubert Ensemble of London. ASV, recorded at Champs Hill, West Sussex, Nov. 5-6, 2001

Finally, we have the best performance I've encountered of the first movement, the one that really seems to grasp that there's an active struggle taking place, and the stakes couldn't be higher: Is it possible to hear and piece together a reality that's physically and emotionally sustainable?

i. Moderato

Bernard Roberts, piano; Chilingirian Quartet (Levon Chilingirian and Mark Butler, violins; Csaba Erdélyi, viola; Philip De Groote, cello). EMI, recorded in London, July 22-24, 1985

Still unanswered in my mind is the therapeutic question of whether it's truly possible to construct a new sense of belief and purpose out of music. At the least, I guess, like chicken soup, it couldn't hurt.

#

No comments:

Post a Comment