i. Einfach (Simple)

ii. Sehr rasch und leicht (Very quick and light)

-- Noch rascher (Still quicker)

-- Erstes Tempo (First tempo)

-- Wie im Anfang (As at the beginning)

iii. Hastig (Hurried)

-- Nach und nach immer lebhafter and stärker (Bit by bit ever livelier and stronger)

-- Wie vorher (As before)

[i. 0:01; ii. 1:59, 2:53, 4:19, 5:07; iii. 5:57, 7:51, 9:09]

Radu Lupu, piano. Live performance in Amsterdam, May 29, 1983

[i. 0:01; ii. 1:59, 2:53, 3:55, 5:11; iii. 5:55, 7:38, 8:44]

Vladimir Horowitz, piano. Live performance in Constitution Hall, Washington, D.C., Apr. 22, 1979

[i. 0:01; ii. 1:31, 2:25, 3:55, 4:43; iii. 5:18, 7:24, 8:50]

Alicia de Larrocha, piano. RCA, recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York City, Nov. 8-9 & 11, 1994

[i. 0:01; ii. 1:15, 2:03, 3:15, 4:00; iii. 4:28, 6:09, 7:30]

Imogen Cooper, piano. BBC Music, recorded live in Wigmore Hall, London, May 28, 1994

A TIP: If you continue reading, a feeling may gradually overtake you that we're never going to come back to these musical examples. Surprisingly, this is not true! At the end, there's a section suggesting kinds of things to consider in listening just to the 38-bar "Einfach" section reproduced in its entirety up top.by Ken

Some of you may have noticed that the rendering by the fine English pianist Imogen Cooper of what I'm calling "opening sections" of Schumann's Humoreske which we heard earlier today in "post under construction" form ("Before we hear Schumann's Humoreske, might we wonder: What the heck is a 'Humoreske'?") was a Sunday Classics "encore presentation," dating back to last summer, when the news of Imogen C (born August 1949) becoming Dame Imogen occasioned a series of posts -- specifically, in the July 25 "post tease" "A special artist finds her way into our Brahms piano party."

UM, WHY (AGAIN) ARE WE LISTENING TO THE HUMORESKE?

Lupu in 2011 [photo by Jennifer Taylor/New York Times]

We're remembering the Romanian-born pianist Radu Lupu (born in November 1945), who died April 17 at the age of 76, and remembering him in (I think) the best way, by listening to and pondering some samples of his piano-playing. The inspiration for those samples came from The Guardian's Andrew Clements, who in his Lupu remembrance proposed "Five key performances" for us to listen to, which I thought we might enjoy listening to together.

In "Radu Lupu (1945-2022) [1]" (May 2), we knocked off the two concertos on Andrew C's list, his first and fourth recommendations:

• a really terrific 1990 video performance of Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 19 in F, K. 459, a piece that perennially lurks just under the rank of the greatest of Mozart's piano concertos -- except when a team of performers get beneath its ever-so-harmonious surfaces to bathe us in its still-deeper-lying harmoniousness, in which connection we paid aural tribute to that master of the Mozart piano concertos Rudolf Serkin, hybridizing a performance from his recordings from 1961 (with George Szell in singularly harmonious temper) and 1983 (with Claudio Abbado). Although for me the heroes of that K. 459 are conductor David Zinman and the inspired young players of the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie, who conveyed such abundant joy in the piece's supple phrases, there's no doubt that Lupu was there pitching in;

• and a really terrific performance of a wildly different piano concerto, the dark and dangerous one that emerged from what its composer had hoped would continue evolving into his deeply-aspired-to first symphony: Brahms's First Piano Concerto in D minor, Op. 15. The performance, however, wasn't the one Andrew C directed us to: an audio broadcast of a 1994 Tokyo performance with Lupu and the NHK Symphony under Wolfgang Sawallisch. We heard it, and it's fine, but I don't hear either the soloist or the conductor, let alone the soloist and conductor in combination, making any special sense of what is for me an exceedingly difficult work to realize fully. I also enjoyed a 1996 video performance I stumbled across, from Helsinki, with Jukka-Pekka Saraste leading the Finnish Radio Symphony in a quite stylish account.

What blew me away, though, was a 1983 audio broadcast in which conductor Klaus Tennstedt energized the London Philharmonic into bringing to beautiful, blazing life to even the darkest corners of this huge, easy-to-underthink piece. Again, Lupu delivered a performance that fit right in, and with his formidable technical equipment rose to some challenges that other pianists might not have. It's a Brahms D minor Concerto I'll definitely be returning to.

THEN IN "RADU LUPU (1945-2022) [2]" (May 8) WE DEALT . . .

. . . with "The Schubert picks from Andrew C's list," his fifth and second. Yes, we heard them backwards (as Sunday Classics veterans are only too aware, we often do things backwards here), leading off with --

• the late-Schubert Fantasy in F minor for Piano Four Hands, D. 940 in a 1984 Snape Maltings recording with Lupu's American near-contemporary Murray Perahia. Andrew C calls it "one of the greatest piano-duet recordings of all time," which isn't what I hear, but we do have two high-quality pianists with enough tempermental affinities to make a plausible team and enough disaffinities to keep them from slipping into routine -- and for my ears, the piece itself takes it from there. It's a work whose haunting beauty would be almost impossible to imagine from any source except the ridiculously young "late" years of Schubert.

• Finally, we dipped our musical toes into the simultaneously earthy and rarified world of those two sets of four each small-scale masterpieces, the Schubert impromptus. Andrew C directed us to a 2012 Moscow live performance of the second set, D. 935 (Op. posth. 142), and we heard that, but Andrew notes that Lupu "also recorded the Impromptus in 1983 for Decca." (The record was released in 1983 but is credited as having been recorded in Hamburg in June 1982.) And I thought it would be intereting to complement the 2012 performance of D. 935 with the 1982 account of the earlier set, D. 899 (Op. 90 -- yes, actually published in Schubert's lifetime).

I'm not sure I made clear that I enjoyed the Lupu impromputs -- a smart choice of Andrew C's. I'm also not sure how clear I made it that I still have reservations about Lupu's impromptus, from both 2012 and 1982. They're beautiful and accomplished, and certainly present a viewpoint about this music. But what I get is mostly a series of moods, or maybe trances. And I keep coming back to a quote I encountered in a YouTube Lupu posting:

"Everyone tells a story differently, and that story should be told compellingly and spontaneously. If it is not compelling and convincing, it is without value."This quote still puzzles the hell out of me, because: (a) It sounds like a statement of musical principle which I could support enthusiastically, and yet (b) it's almost the exact opposite of what I hear in Lupu's playing. [NOTE: The "(a)" part is a hopefully-clarifying afterthought-addition to the "because" clause. -- Ed.]

-- Radu Lupu, quoted by the YouTube poster of a Lupu

Brahms First Piano Concerto with Jukka-Pekka Saraste

In posting the two sets of Schubert Impromptus last week, I shadowed the Lupu performances with Artur Schnabel's famous 1950 EMI recordings of both sets, and then for D. 899 tacked on a cluster of performances of three of the four -- a not-quite-random samping of impromptus played by some of the unquestioned master pianists of the 20th century: Vladimir Horowitz, Arthur Rubinstein, Sviatoslav Richter.

Among other things, from Horowitz we had a 1987 Vienna performance of the G-flat major Impromptu, D. 899, No. 3, which we first heard in a May 8 mini-post ("Since in 'Radu Lupu (1945-2022), part 2' we'll be hearing both sets of Schubert impromptus, maybe this'll help get us in the mood") and which I described in the later post as "riveting, possibly life-altering," and for Rubinstein I made a point of including all four of his recordings -- from 1928 to 1961 -- of the A-flat major Impromptu, D. 899, No. 4, by way of illustration that with this master musical story-teller, the story he told and the way he told it may have undergone substantial evolution over those 33 years, but the need to tell a story in music, compellingly, seemingly spontaneously, and convincingly, can become if anything more urgent.

WE CIRCLED THIS POINT WITH SCHUBERT'S GASTEIN SONATA

I imagined last week that we might want to talk cases-in-point with some of the Schubert impromptus, but now I don't think so. I would rather just encourage you to go back and listen (or relisten) to some of last week's performances of Schubert impromptus, and ponder the differences between, say, the Lupu and Schnabel performances, or between those and the assorted Rubinstein, Horowitz, and Richter ones.

Obviously -- at least I think it's obvious -- we all hear music differently. In fact, there's probably less general agreement than we usually think as concerns what we're listening for, a question I've thought I was on the verge of venturing ever so cautiously into since last October, when the point threatened to stand in our path, up in connection with Schubert's Gastein Piano Sonata: "Do we dare let Schubert's Gastein Sonata nudge us into the question of what we're looking for in music?" (Oct. 21, 2021).

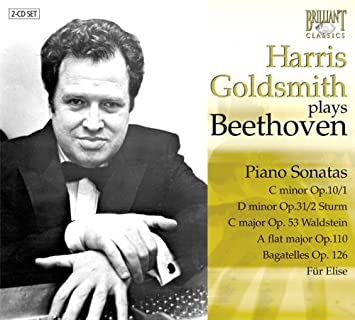

Perhaps ironically, back then the case I wanted to argue wasn't the "Schnabel is tops" one. It wasn't an anti-Schnabel case either. What I wanted to establish, in bald contradiction of my old friend the pianist and critic Harris Goldsmith, who hated Emil Gilels's 1960 RCA recording of the sonata, in fact thought it was emblematic of the problematic run of then-modern performances of the Classical repertory, and held up as the exemplar, despite all their problems, the Schnabel recordings.

I still don't suppose I can make you understand the degree of respect I had (and have) for H.G.'s depth of knowledge and sensitivity in the broad Classical and Romantic repertory. (As I point out from time to time, he was also a terrific pianist. And he was always at his most "alive" when he had a playing engagement.) But I heard (and hear) in a lot of Gilels's surprisingly subtle performances, many of which I've been living for for quite a while now, a coherent and compelling aural "vision" for the musical stories he told in a wide range of repertory. I was especially taken with that recording of the Gastein Sonata, which was not a performance I'd lived with all those decades -- I'm not sure I'd ever even heard it before the round of listening I did for that series of posts. It happens that I'd never really had the occasion to listen to and think about the piece with any seriousness. And in the process of thinking about how its four really disparate movements (I'd been dragged into the whole subject by a mesmerizing hearing of a Richter recording of the second movement) required not just disparate individual understandings but a "vision" of how they fit together, of what kind of artistic whole they might form.

So it's entirely possible that I may be missing Lupu's artistic visionariness as surely as I'm thinking H.G. missed Gilels's. As mystified as I may be by the music lovers who profess to hear great insights in Lupu's playing, that doesn't mean I'm right and they're wrong. I've really been trying to challenge myself to listen with fresh ears, and that's why I was so happy with Andrew Clements's suggestions of things to listen to.

At some point while these issues have been swirling in my head, a quote that I assume came from my e-mailbox seemed to me quite pertinent. I thought it was in the e-newsletters of either James Clear (every Thursday) or Adam Grant (roughly monthly), but haven't been able to turn it up in either archive. The gist was that when we're confronted with an argument for a viewpoint different from our own, the proper test isn't whether the argument converts us but whether it inspires us to think anew about the issue(s).

THOUGHTS FROM LUPU'S ONETIME RECORD PRODUCER

Just today I stumbled across an excellent new source for thinking about Lupu: an April 20 remembrance post by Michael Haas on his Forbidden Music blog. Haas was Lupu's producer for a number of years while the pianist was under contract to Decca Records (including the 1982 Schubert impromptus, by the way!), having joined the company at an unusually young age and without much record-producing experience. What he had was a formal Viennese education in piano.

I had studied piano in Vienna’s Music Academy and latterly at the Conservatory and my head was full of the specifically piano-esque. It had been an education that believed teaching fingers to play the piano was all that was necessary. The piano teachers were fairly poor at teaching music. If they had been better, it would have become obvious that the fingers would follow.Another thing Haas brought to Decca was enthusiasm for Radu Lupu, and after a couple of years of serving as "assistant producer on a number of opera recordings" -- "I sat in on numerous recording sessions produced by colleagues and fetched teas, coffees and ordered taxis" --

I was entrusted with my first recording as producer: Radu Lupu and Schubert. It was an insane idea from the Great-and-Good of Decca who obviously wanted me to sink or swim. Thinking back to these sessions in Kingsway Hall in Central London, I wonder how I didn’t sink.He understands his responsibility for landing himself that precarious situation, for his thoroughness at "letting everyone at Decca know that of all the Decca pianists, Lupu was the one I most admired."

Unknown to me, nobody else at Decca wanted to work with him. He was notoriously difficult, neurotic, insecure and in a constant state of frustration.And Haas proceeds to provide an insider's perspective on what made Lupu so hard to produce, much of it having to do with those views I've expressed such puzzlement about, regarding musical story-telling and spontaneity, and on the basis of them producing performances that are compelling and convincing. The playing may sound totally unspontaneous to me, but apparently it was spontaneous enought that for an operation as theoretically simple as replacing a fluffed note in a recording take, there was unlikely to be another take in which the needed note was produced in a way that could simply be inserted in the one in need of fixing. Lupu's proposed solution would be to go in and do another take!

Haas has a lot more to say about the difficulties of recording Lupu, but the admiration is for real.

Lupu had a total command of structure and though he was constantly fretting about it, an astonishing technical command of the instrument. But it was this sense of architecture that made him different and explained why he hated recording. A performance is a narrative. It has a beginning, a middle and an end and Lupu’s attraction to composers like Schubert and Beethoven was because these were particularly challenging narratives to construct.There's always a difficulty in applying the "architectural" metaphor to music, because while structure is clearly an important component of art music, the kind of structure it is isn't in any way, shape, or form like architectural structure.

Any building constructed in any way that resembles the way that, say, Beethoven constructed a sonata, would collapse in seconds -- assuming you somehow managed to build enough of a structure to even stand for seconds. And any story-teller, musical or otherwise, who tried to put together a story the way an architect designs a building couldn't hold an audience for 10 seconds.

So whatever "total command of structure" it is that Lupu had, I'm maybe not surprised that it doesn't have much to do with what I listen for in music, or that his musical architect's command of spontaneity doesn't correspond to what I would hear as communicative spontaneity. Do I have to point out that spontaneity is not a quality valued in architects. Freshness, yes, certainly, possibly even an occasional architectural detail that has a look of spontaneity. But any structural element an architect incorporates in a design had damn well better satisfy every requirement of structural integrity that applies to the job.

STILL, I EAGERLY RECOMMEND MICHAEL H'S BLOGPOST

I learned a lot from it, and it gave me a lot to think about in connection with recordings generally and Lupu's recordings in particular. And I plan to explore the Forbidden Music blog. Beyond Michael H's extensive experience as a producer and executive for Universal Music (into which, as I understand the story, Decca was folded) and later Sony, and some occasional ongoing record-producing gigs, his professional life has moved in other interesting directions. The blog itself back to, and takes its name from, the book of his that was published by Yale University Press in 2013: Forbidden Music: The Jewish Composers Banned by the Nazis. A paperback edition followed in 2014, and I gather that most of Michael H's professional life these last couple of decades has been in this general field. According to his bio on the forbiddenmusic.org website, he's "now engaged as Senior Researcher, co-Founder and Chair of the exil.arte Centre, based at Vienna’s University for Music and Performing Arts," where he "is responsible for finding, and overseeing the digitisation and dissemination of 'exiled' musical estates acquired by exil.arte."

MEANWHILE, BACK AT SCHUMANN'S HUMORESKE

You'll be relieved to hear that we're not going to push our pursuit of Schumann any further this week, or at least today. But I think the four clips at the top of this post, ranging in duration from 8:33 to 10:27 -- out of a total of some 25-29 minutes -- give us a chance to do some sampling of the piece, and some back-and-forth-ing. (I'm looking forward to doing some of this myself.)

Schumann's great piano suites are such complex musical organisms (hmm, now I wonder whether "organisms" are any more useful a metaphor for music than "architecture" -- offhand, I think they actually are) that I don't want to venture in without some sort of preparation. They're chockful of structural issues, but again none of them in any way resemble the kind of structural issues that architects deal with in building buildings.

With the Humoreske we have to be especially careful about breaking it into sections -- it certainly doesn't have "movements." CD editors are generally able to find moments for track placement, but there really are no breaks in the piece. In fact, the one that comes closest is the one we see at the end of the first printed page, following the opening "Einfach" ("Simple") section, which is why I'm treating it as a "section," even though hardly anyone else does. And I think it can make a difference in how we perceive this wonderful, and for all its seemingly ridiculous simplicity extremely problematic, section (just listen to how different our four performances of it are) -- if on the one hand it's an introduction to the piece as a whole, or on the other hand the first part of, er, a musical structure that spans everything up to the start of the "Hastig" ("Hurried") section.

In the matter of structure, we have to consider as well that Schumann is perfectly capable of providing a dramatic shift in musical movement without changing the tempo or introducing an expressive marking, as we'll hear him do throughout the individual "sections." In our third "section," for example, the one that begins with the "Hastig" ("Hurried") marking, before the "Wie vorher" ("As before") marking there's an extended sectin built mostly of two-hand half-note chords, most sustained over multiple bars, and at the end of the "Wie vorher" section there's a nine-bar mini-section (really only eight bars, since the first and last "notes" are quarter-note rests) marked with the seriously slow tempo Adagio, mostly P or pp, though with a couple of marked crescendos -- and ritards marked over the third- and fourth-to-last bars.

If you want some hints as to the "hidden" complexity of the "Einfach" section, I think you can see, even if you don't read music, that almost the whole of this 38-bar gem follows pretty much the same simple format: three voices, all sounding single notes -- an upper voice almost entirely in half-notes; at the other end a bottom voice, also nearly all in half-notes, offering tonal underpinning and harmonic anchoring; and a middle voice that consists mostly of falling-pattern eighth-notes, which is to say a quarter the length of all those half-notes, with in almost every bar an eighth-note rest on the beginning of the beat.

The piano, we all know, is an instrument that gives you only a single crack at each note; however you choose to strike it, you basically get that stroke and nothing more for the indicated duration of the note -- unlike, say, a woodwind or brass instrument where you can output as much sound as your breath will create. And that top note is the melody! A simple one, to be sure, but also, at least potentially, quite a lovely one. And yet it has to be sustained throughout its portion of the melodic arc with just that one keystroke, during which fingers from one or the other hand are sounding all those eighth notes, which need to be sounded and phrased as if they were being produced by a single voice.

Is it any wonder, then, that those evenly spaced half-notes of the upper-voice melody tend to get overstruck, as if they're meant to be accented, which can reduce the lovely little melody to a series of galumphingly disconnected, overly accented single notes -- sort of like the way children may beat out "Mary Had a Little Lamb" or "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star" in their first week of piano instruction. If you're thinking, in terms of sustaining the lovely little treble melody, "What about the pedal?," well, what about the pedal? Yes, it will sustain notes; that's why it's called the "sustaining pedal." But it won't just sustain the top and bottom half-notes; it will also sustain all those brief-duration eighth-notes.

One thing more accomplished pianists have going for them is the knowledge that there really are a zillion ways to strike a piano key, and even those zillion ways vary considerably according to where the keys lie on the keyboard -- from bottom to top, those keys not only sound but work very differently, and so do black vs. white keys. So a really good pianist does have some tools for getting somewhat different kinds of sound, not just louder or softer, out of different keys. Another tool, or rather more of a strategy, is to take a slightly (or maybe not so slightly) faster tempo, thereby shortening the length of time that those upper-voice melodic notes have to be sustained. Both our female pianists seem to have thought of this.

There's also an issue with those beginning-of-the-beat eighth-note rests. For some reason, a lot of pianists seem to think this presents an opportunity to stretch the start of the beat, kind of the way we're always told authentic Viennese musicians stretch the first of the three beats that make up a bar of waltz. I think it sounds horrible, and does further violence to the melody the top voice is trying to sing. But then, I also hate the extent to which so many pianists torture Chopin's musical lines by lengthening or shortening specified note values, because they've been taught that Chopin is meant to be played with "rubato" -- i.e., with "stolen" rhythmic values. But rubato doesn't mean rewriting the rhythmic profile. Yet you'll hardly ever hear a performance of Chopin's First Ballade, the great G minor, one of the great artistic creations of the human mind, that isn't so drastically and unceasingly pulled and pushed as to turn the whole thing into a pile o' crap.

But speaking of tempo and rhythm, the performer still has to decide on a basic tempo, to start the piece at least. There is a metronome marking, quarter note = 80, which suggests a kind of moderate Andante -- not "slow" so much as a walking (or "going") pace; each two-beat bar would call for a pair of those. (Since I'm working from the fine old Dover reprint of the long-serving old edition of Schumann's piano works edited by his wife, the great pianist Clara Schumann, and I've never troubled to check out just how reliably those edition represent Robert S's intentions, I should really consult the more scholarly editions that I'm sure have come into being to see how authentic those metronome markings are.)

There's also some marked fiddling with tempo: ritards (slowdowns) in bars 19 and 22, with no corresponding re-speedups -- at least until the marking of "Etwas lebhafter" ("Somewhat livelier") at bar 30, at which point the mostly-all-half-note melodic line energizes -- just how much does the performer want to slow down earlier on and then speed up at bar 30. Then there are ritards indicated in each of the three bars preceding the final B-flat major chord; how moderate or extreme ought they to be?

There aren't a lot of dynamic markings, which perhaps lays greater weight on the ones there are. The very beginning is marked "p" for "piano" (soft); then after the double bar (why a double bar there? hmm) at bar 10 there's a marking of "pp" for "pianissimo" (very soft). There are occasional markings of "dim." for "diminuendo" (get softer) and a number of "crescendo"s (get louder) marked with the horizontal arrow sign, which gives the performer some indication of how long a span the loudening is meant to take -- all these things require decisions from the performer, as well as what subtle dynamic adjustments the performer wishes to add to the mix.

There aren't a lot of articulation markings. For the mostly-half-note top and bottom voices there are pretty regular two- or three-bar slurs throughout, to suggest basic phrasing. But for those three-eighth-note down figures in the middle voice, in the first six and a half bars there are both slurs and staccato markings, a balance the performer has to work out. Thereafter there are neither slurs nor staccato markings appear -- this could represent a change, or it could just represent an assumption of "and so on." Here too it would be helpful to consult a well-edited modern edition; the editor might be able to tell us that the "etc." format is common for either the composer or the period; then we just have to know how much we trust this editor.

Those are just some things to think about in this minute-and-a-half to two minutes of music, music that is in so many ways so ridiculously simple, and that's directed to sound "simple," or be played "simply." By the way, what do we think of our four pianists' idea of simpleness? I'll admit that I'm not entirely persuaded by the two men's.

AGAIN, MOSTLY WE HAVEN'T TOUCHED ON ANYTHING

THAT GOES BEYOND THE 38-BAR "EINFACH" SECTION

As the Humoreske proceeds, Schumann has a world of other possibilities to incorporate, and the performer has all manner of considerably more complicated, denser, and more dangerous puzzles to puzzle out.

Probably we should have devoted a whole post to this, really covering a modest chunk like our three "sections," and having the opportunity to look at some of our performers' choices. Actually, that's what this post was supposed to be. Hey, sometimes things work out and sometimes they don't.

STILL TO COME: We have to finish up with Schumann

And we should probably consider Andrew C's proposition in commending Lupu's 1983 Humoreske to our attention -- that it's "a perfect example of Lupu’s ability to transform a relatively modest work, by no means one of Schumann’s greatest, into something very special indeed." It could just be me, but I flash back to the Mozart piano concerto, No. 19 in F, that we heard earlier. I guess you could say that it's "by no means one of Mozart's greatest," and the analogy I suggested between it and the concerto that followed, the great D minor, No. 20, on the one hand, and on the other hand the Beethoven Fourth and Fifth Symphonies, where the later work can easily overshadow the earlier one -- not because of any deficiency in the earlier work but because of the breakthrough ambitions represented by Mozart 20 and Beethoven 5.

I still say you couldn't write a better concerto than Mozart 19, or a better symphony than Beethoven 4. In the Humoreske we have one of the great creative minds working in a format that suited him so well: an extended piece for solo piano, of which he had such an intimate understanding. I can't help wondering whether this is really a case of the performer making the piece sound "very special" -- or vice versa.

#

No comments:

Post a Comment