of sorts) with yet another stupendous operatic scene

[TUESDAY EVENING NOTE: Since initial posting, this piece has undergone variously significant updating scattered all through it, with possibly more to come -- if I get up the courage to wade into the thing.]

You'd think it'd be a snap to find a shot (no pun intended) of the Prison Scene from Don Carlos. Hah! In the spirit of last week's makeshift "Mélisande tower" (which I'm embarrassed to report we're going to be seeing again), I've wound up making do with, you know, "a prison."

VERDI: Don Carlos: Act IV [or III], Scene 2, Death of the Marquis of Posa ("Che parli tu di morte?" . . . "O Carlo, ascolta" . . . "Io morrò, ma lieto in core")

Recitative, "Che parli tu di morte?" -- and surprise!

DON CARLOS [trembling]: Why do you talk of death?

RODRIGO: Listen! Time grows short.

I have turned back onto me the terrible thunderbolt.

Today it's no longer you who are the rival of the king.

The bold agitator for Flanders -- it's I!

DON CARLOS: Who could possibly believe that?

RODRIGO: The proofs are tremendous!

Your papers, found in my possession,

are clear testaments to rebellion,

and on this head for certain

a price has already been set!

[Two men are now seen descending the prison staircase: One of them is dressed in the garb of the Holy Office; the other is armed with an arquebus. They stop for a moment and point out to one another DON CARLOS and RODRIGO, by whom they are unseen.]

DON CARLOS: I will reveal everything to the King!

RODRIGO: No, save yourself for Flanders!

save yourself for the great work that you will have to accomplish.

A new golden age you will cause to be reborn;

you were meant to reign, and I to die for you!

[The bearer of the arquebus now takes aim at RODRIGO and fires.]

DON CARLOS [stupefied]: Heavens! Death! but for whom?

RODRIGO [mortally wounded]: For me!

The vengeance of the king couldn't be delayed!

[Falls into the arms of DON CARLOS]

DON CARLOS: Great God!

Recitative, "O Carlo, ascolta"

RODRIGO: Oh Carlos, listen! Your mother, at San Yust,

tomorrow will expect you -- she knows everything.

Ah! the ground gives way beneath me --

my Carlos, give me your hand --

Aria, "Io morrò, ma lieto in core"

I die, but light of heart,

since I have thus been able to preserve

for Spain a savior.

Ah! do not forget me!

Do not forget me!

You were meant to rule,

and I to die for you!

Ah! I die, but light of heart,

since I have thus been able to preserve

for Spain a savior.

Ah! do not forget me!

Ah! the ground gives way beneath me!

Ah! do not forget me!

Give me your hand . . . give me . . .

Carlos, farewell! Ah! ah!

[RODRIGO dies. CARLOS falls, in despair, on his body.]

["O Carlo, ascolta" at 1:37; "Io morrò" at 2:39] Robert Merrill (b), Marquis of Posa; with Jussi Bjoerling (t), Don Carlos; Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, Fritz Stiedry, cond. Live performance, Nov. 11, 1950

["O Carlo, ascolta" at 1:29; "Io morrò" at 2:31] Robert Merrill (b), Marquis of Posa; with Giulio Gari (t), Don Carlos; Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, Fausto Cleva, cond. Live performance, Apr. 4, 1959

by Ken

I mean it: no talking. Or hardly any. Otherwise we'll never get anywhere. (If you read on, you may wonder at the application of this theory. You would be entirely within your rights. No refunds will be available, however. Meanwhile, I'm thinking that if I just go ahead and post this "as is," it'll be sufficiently embarrassing to force me to go back and at least fill in the more obvious gaps. I'm not confident that much can be done with the stuff between the gaps.)

Some other time I can explain how these particular scenes took up lodging in my brain. One of them, as I trust you've noticed, is the Prison Scene from Verdi's Don Carlos (the first scene of Act IV in the original five-act version; of Act III in the truncated four-act one), which I've heard pared down here to just the actual death of Rodrigo, the Marquis of Posa. We're going to be hearing a bunch more times in more proper context: with what precedes it in this scene . . . .

THAT IS, RIGHT AFTER WE HEAR OUR OTHER SCENE,

THE ONE WE BEGAN LISTENING TO LAST WEEK . . .

. . . which is to say, Act III of Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande. Just as a reminder, what we were listening for ("Inaugural Edition, no. 5: Post tease: Has any operatic act begun more beautifully? (Not to mention suggestively?") was the moment, in Scene 3 of the act, when Pelléas, newly emerged -- in the company of his significantly older half-brother Golaud -- from the suffocating atmosphere of the subterranean vault beneath the dank castle of their grandfather, King Arkel, gulps in fresh air, luxuriating in his recovered ability to breathe.

Under this post's strict No Yammering rule, I really shouldn't be explaining much further, so I'll just say that, as much as Don Carlos is woven into my DNA, the origin story here doesn't begin with me craving to dip into it. It wasn't even on my mind. What I was playing with was my LaserDisc players -- four of them, if you can believe it -- to see whether at least one might be coaxed to, you know, play some LaserDiscs, of which I have quite a large collection, including a lot of stuff I'd love to be able to look at. Now, it just so happened that the first one of them I cracked open turned out to contain one of the two LDs that make up Herbert von Karajan's 1986 Salzburg Easter Festival production of the opera (with which Maestro K had a long history). I didn't remember exactly how that came to pass, but never mind -- it seemed only logical to use that as my guinea-pig LD. Eventually, to jump ahead in the story, it turned out that the other LD was lodged in another of the spectral LD players.

To make matters truly comical, it further developed that each disc had a cracked side! Isn't this special? (Did I know this way back when? I don't think so, but I don't remember!) I reckoned, though, that the un-cracked side might well be playable, since, according to my recollection, two-sided LDs are actually made up of two thinner discs bonded together, from which it seemed entirely plausible that the two as-yet-uncracked sides might yield up some watchable and listenable content. And I honestly didn't recall ever having looked at any of that performance, in good part, I suppose, because the cast didn't look that encouraging, and neither, for that matter, did the musical state of mind Maestro Karajan was in in those days, perhaps typefied by the idea of performing Verdi operas with the utterly-un-Italian Berlin Philharmonic.

In case you were concerned about my having to soldier on with a half-cracked copy of the Karajan Don Carlo LDs, I can report that when I resumed the stalled project of reshelving my LDs -- the undertaking that had prodded me to try to figure out once and for all whether I could actually play the confounded things -- I discovered that there's a perfectly fine copy of the Don Carlo right in place among the LD Verdi operas. (No, not the one in the picture. That's not mine.) The damaged copy, it appears, had always been a surplus one. Whew!

With the first two LD players I tried to get play one of the Don Carlos LDs (why not use them? since they were already half-kaput, how much more was there to lose?), it was nothing doing. But player no. 3, once I was able to get it up operational, despite difficulties in operating some of its controls, showed signs of function. I decided to let it try to play something. And given my choice of the two uncracked Don Carlo sides, the choice was Side 4, which contained the Prison Scene (Scene 2 of Act III in this four-act rendering) and the compact final act. I don't automatically gravitate to the Prison Scene -- as far as I can recall, for all the time we've spent here at Sunday Classics diving into and burrowing around Don Carlos, I don't believe we've ever dipped into it -- it's not as if I don't love it, dating back to my first encounter with the opera, about which more anon.

I'm not going to go into great detail, but I wasn't prepared for the sounds that came out. Here in 1986 poor José Carreras seemed all throb and wobble, with a minimum of real singing tone left in that once-so-beautiful voice, and Piero Cappuccilli, never exactly a top-drawer Verdi baritone, sounded worse. Often enough in earlier years he'd gathered his resources enough to achieve a level of, well, okayness. Beyond the very nice work I remembered from him as Antonio the gardener and Masetto the buffoon in the Giulin-EMI recordings of Mozart's Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni, I'd gotten a surprising amount of pleasure from his Barnaba in the Callas stereo remake for EMI of Ponchielli's La Gioconda. I hadn't much enjoyed anything I'd heard from him during his unexpected heyday as a "leading" Verdi baritone, but I'd never heard anything like this. With the Berlin Phil tootling and sawing away more or less tonelessly, the scene was a ruin.

TOWARD A BACKWARD JOURNEY THROUGH PELLÉAS ACT III

Ernest Ansermet (1883-1969): A miracle worker with Pelléas in New York

Hard on that distressing encounter with Don Carlos performance, and some efforts to scratch a blogpost out of it, perhaps as an effort to get myself back into a blog-productive track, with Act III of Pelléas et Mélisande hanging over me from last week's putative "post tease," I slapped on a DVD from a performance I've had for quite a while but probably never listened to straight through or with careful attention: the 1962 broadcast conducted, in his only-ever appearance at the Met (for a total of five performances of Pelléas in November-December 1962, which thankfully included this broadcast. It hit me, in this foul mood, as something of a miracle.

(To be technical, a couple of months earlier, on September 29 and 30, 1962, during the "inaugural week" festivities of Lincoln Center with the opening of Philharmonic Hall, Ansermet had conducted Met forces in a concert double bill of Manuel de Falla's El Amor brujo and the "dramatic cantata" Atlántida. Though the works were billed as, respectively, a "Metropolitan Opera Premiere" and a "U.S. Premiere," they weren't really Met performances, and there doesn't seem much question that the first Pelléas, on November 30, marked Ansermet's Met debut -- or that the fifth and final Pelléas, the broadcast performance of December 29 from which we're hearing, was also his final Met performance. By the way, his Met Golaud, George London, who had also participated in the Philharmonic Hall Atlántida performances, would be on hand in August 1964 when Ansermet, back home in Geneva, made his second Decca recording of Pelléas, in still-luminous stereo sound, with a first-rate Mélisande and Pelléas in Erna Spoorenberg and Camille Maurane -- still my favorite recording of the opera.)

Definitely worth writing about, but how to do it? From the moment I decided to present the moment of Pelléas's physical release from the unbreathable air of the subterranean vault he'd been traipsing through with his brother Golaud as part of my Inaugural Celebration, I realized that for you to fully appreciate the situation Pelléas finds himself in here in Scene 3, we would need to go back at least partway into (the quite brief) Scene 2, the scene of Golaud and Pelléas in the fetid underground vault.

And then, really, to understand what's going on there between the brothers, or at least as much as we're able to understand, we need to go back at least partway into the much longer Scene 1 -- say, to the point where Golaud happens upon his brother outside the castle tower where Golaud's wife, Mélisande, has her chamber and finds the young people engaged in a, shall we say, provocative interchange that clearly sets off alarm bells already ringing inside his head, something we're going to remember, I think, when we see Golaud leading Pelléas in Scene 2 along the precarious precipice And of course to have a proper context for the goings-on between Pelléas and Mélisande, we would in fact need to go back to the top of the act, where we the audience meet Mélisande alone in her chamber combing her hair -- which we in fact sampled in that last post.

And that backward progression -- maybe backwards, or maybe forward -- is what I thought we would do as our follow-up to the earlier post. I think it's still an interesting idea, and it could yet happen. For now we're just going to hear these first three scenes of Act III, right up to the start of Scene 4 (perhaps you can think of another operatic composer whose powerfully dramatic orchestral scene-change interludes we always try to hear in as complete a form as possible?) in this special performance. And in this performance I have particular pangs about not continuing on into Scene 4, since there we finally meet "Little Yniold," Golaud's young son from his first marriage, whom we've heard about a couple of times in the opera but not yet seen, and the Yniold of this performance is none other than the 24-year-old Teresa Stratas, who would go on -- among a career's worth of striking accomplishments -- to be a singularly memorable Mélisande, a role one might think she was born to play.

Scene 4, by the way, which finds us back in front of the castle, is of similar length to Scene 1, so that Act III's two "long" scenes bracket the pair of short ones. Collectively they may be thought of as depicting "The Unhinging of Golaud," whose suspicion that something is going on between Pelléas and Mélisande is well established by the time he walks in on their frolicking in Act III, Scene 1 -- where, contrary to his vehement protestations, he doesn't believe at all that what he's witnessing is "child's play," something I've found myself over the years more and more oppressively aware in Scene 2 as Golaud leads Pelléas in Scene 2, for no reason we know of, into those vaults beneath the castle, along the precarious precipice of the dank and near-bottomless chasm where at any moment a tragic "accident" might occur, accidentally or otherwise. The only danger Pelléas seems aware of in the unbreathable atmosphere of the subterranean vault is breathability, setting up the breathtaking moment of his regaining his breath. Is he really that unaware of the more immediate physical danger he escaped with his rush to daylight? Not even a little, maybe subsconsciously?

In a way, I'm not entirely sorry to sneak away before Scene 4 of Act III. SPOILER ALERT: Golaud's abuse of Yniold, forcing him to spy on his stepmother and uncle, is painful to watch. At that, it's scant preparation for the utterly unspeakable horrors we'll witness in Act IV. I say we pretend we don't know about any of that as we listen to this special performance of the first three scenes.

DEBUSSY: Pelléas et Mélisande: Act III, Scenes 1-3

Here's the aforementioned "make-believe Mélisande's tower" from last week.

Scene 1: One of the towers of the castle. A watchman's path passes under a window of the tower.

MÉLISANDE [while she combs her loose hair]:

My long hair descends all the way to the door of the tower --

my hair is waiting for you the whole length of the tower,

and the whole length of the day, and the whole length of the day.

Saint Daniel and Saint Michel, Saint Michel and Saint Raphaël,

I was born on a Sunday, a Sunday at noon.

[PELLÉAS enters by the watchman's path.]

PELLÉAS: Hola! Hola! Ho!

MÉLISANDE: Who's there

PELLÉAS: Me, me, and me! What are you doing there at the window, singing like a bird that's not from here?

MÉLISANDE: I'm fixing my hair for the night.

PELLÉAS: Is that what I see on the wall? I thought you had a light.

MÉLISANDE: I opened the window. It's too hot in the tower. It's a beautiful night.

PELLÉAS: There are countles stars. I've never seen as many as tonight. But the moon is still over the sea.

Don't stay in the shadow, Mélisande. Lean out a little, so I can see your loose hair.

MÉLISANDE: I look horrible this way.

PELLÉAS: Oh! Oh! Mélisande! Oh! You are beautiful! You are beautiful this way. Lean out, lean out! Let me come closer to you!

MÉLISANDE: I can't come closer to you. I'm leaning as much as I can.

PELLÉAS: I can't climb higher. At least give me your hand tonight, before I go away. I'm leaving tomorrow.

MÉLISANDE: No, no, no!

PELLÉAS: Yes, yes, I'm leaving. I'll leave tomorrow.

Give me your hand, your hand, your little hand on my lips.

MÉLISANDE: I won't give you my hand if you're leaving.

PELLÉAS: Give it, give it, give it!

MÉLISANDE: You won't leave?

PELLÉAS: I'll wait, I'll wait.

MÉLISANDE: I see a rose in the shadows.

PELLÉAS: Where then? I only see the branches of the willow that overhangs the wall.

MÉLISANDE: Lower, lower, in the garden, down there in the dark green.

PELLÉAS: It's not a rose. I'll go see right away, but give me your hand first! First your hand.

MÉLISANDE: There, there! I can't lean any farther.

[The young folks continue flirting and teasing. Mélisande's hair tumbles down from her window and Pelléas grabs it and carries on with it like you wouldn't believe (aren't you glad you aren't the stage director and designer and costumer who have to figure out how to stage all this?), despite a warning from Mélisande that "someone could come." It turns out that she has doves in her chamber, which are frightened by the goings-on and fly out the window and off into the darkness -- never to return, Mélisande is sure. (Pelléas doesn't see why not.) With increasing urgency Mélisande urges Pelléas to let her go, until she hears footsteps.]

MÉLISANDE: It's Golaud! I think it's Golaud! He's heard us.

PELLÉAS: Wait! Wait! Your hair is entwined in the branches. It got caught up in the darkness. Wait! Wait! It's dark.

GOLAUD [entering along the path]: You are children! Mélisande, don't lean so out the window, you're going to fall. You don't know that it's late? Don't play so in the dark. You are children. What children! What children!

[He leaves with PELLÉAS. CURTAIN]

Orchestral interlude

Scene 2: The underground vaults of the castle.

Enter GOLAUD and PELLÉAS.

GOLAUD: Take care -- this way, this way. You've never penetrated into these vaults?

PELLÉAS: Once, some time ago. But it was a long time.

GOLAUD: Well, here is the stagnant water I was talking to you about. . .

Do you smell the scent of death that's rising?

Let's go up to the edge of that rock that juts out, and lean over a little; it'll come and smack you in the face. Lean over. Don't be afraid -- I'll hold you. Give me -- no, not your hand, that could slide, your arm. Do you see the chasm, Pelléas? Pelléas?

PELLÉAS: Yes, I think I see the bottom of the chasm. [With suppressed agitation] Is that the light that's trembling so? You --

[He straightens up, turns, and looks at GOLAUD.]

GOLAUD: Yes, that's the lantern. I was swinging it to illuminate the walls.

PELLÉAS: I'm suffocating here. Let's go out.

GOLAUD: Yes, let's go out.

[They go out in silence. CURTAIN]

Orchestral interlude

Scene 3: A terrace at the exit from the vaults

Enter GOLAUD and PELLÉAS.

PELLÉAS: Ah! I breathe at last! I thought, an instant, I was going to be sick in those enormous caves; I was on the point of falling. In there the air is humind and heavy like lead dew, and thick shadows like a poisoned paste. And now all the air from all the sea!

There's a fresh breeze, see, fresh like a leaf that has just opened, on little green blades.

Hold! They've just watered the flowers at the edge of the terrace and the scent of the greenery and of the dampened roses rises up to here. It must be near noon; they're already in the shadow of the tower. It is noon. I hear the bells sounding, and the children are heading down to the beach to bathe.

Look, there's our mother and Mélisande at a window of the tower.

GOLAUD: Yes, they've taken refuge on the shady side. Speaking of Mélisande, I heard what happened and what was said yesterday evening. I know it was children's games, but that mustn't be repeated. She's very delicate, and she must be taken care of, all the more in that she will perhaps soon be a mother, and the least disturbance could lead to tragedy. It's not the first time that I notice there might be something between you . . . You're older than she; it will be enought to have spoken to you about it. . . Avoid her as much as possible, but without making a show of it at the same time, without making a show of it.

[CURTAIN]

Orchestral interlude

[As noted, we've stuck with the interlude right up to the start of Scene 4.]

[Scene 2 at 14:05; Scene 3 at 17:59] Anna Moffo (s), Mélisande; Nicolai Gedda (t), Pelléas; George London (bs-b), Golaud; Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, Ernest Ansermet, cond. Live performance, Dec. 29, 1962

NOTE: I had it in mind, and guess still have it, to add other performances of this entire bloc of music. Still, this is the performance that really took hold of me -- at a time when I needed just such an experience. Maybe later.

It's still the plan, by the way, to go back and break this chunk down into overlapping component parts, hearing some of the ways in which performers have handled them.

NOW BACK TO POOR CARLOS IN PRISON, HAVING

NO IDEA OF THE HORROR HE'S ABOUT TO WITNESS

Which I mention because one thing I found myself thinking about once I knew that -- for fairly crazy reasons I'm not allowed to explain under the rules for this post -- I was going to be looking at the Prison Scene from Don Carlos was the very fact that Rodrigo is already fully aware, from well before the moment he enters this scene, that with 100-percent certainty he is going to die in the very near future.

And in this context I found myself listening with more interest than I ever have before to the 1954 EMI-RCA recording with Tito Gobbi as Posa, which we might talk about just a little after we hear the clips of this scene I've made.

VERDI: Don Carlos: Prison Scene (Act IV [or III], Scene 2):

Scene 1, Rodrigo, "Son io, mio Carlo" . . . "Per me giunto è il dì supremo" . . . "Che parli tu di morte?" . . . "O Carlo, ascolta" . . . "Io morrò, ma lieto in core"

The prison of Don Carlos. An underground dungeon, in which a few articles of court furniture have been hastily introduced. At back an iron grating, which separates the prison from a courtyard that overlooks it. A stone staircase leads into the courtyard from the upper stories of the edifice. CARLOS is seated, his head resting on his hand, buried in thought. RODRIGO enters and speaks aside to some of the officials, who immediately withdraw. He mournfully contemplates CARLOS. At a movement on the part of RODRIGO, CARLOS looks up.

Recitative, "Son io, mio Carlo"

RODRIGO: It's I, my Carlos!

DON CARLOS [extending his hand]: Oh Rodrigo, I'm so grateful

to you for coming for Carlos in prison!

RODRIGO: My Carlos!

DON CARLOS: You know it well! All my strength abandons me!

Love for Elisabeth tortures me and kills me!

No, I am of no more use for the living. But you,

you can still save them! Oppressed, no, they'll no longer be!

RODRIGO: Ah, let be known to you the extent of my affection!

You are to leave this horrendous tomb!

I am happy yet if I can once more embrace you!

I have saved you!

DON CARLOS: What are you saying?

RODRIGO [with emotion]: It's necessary for us to say farewell here!

[DON CARLOS remains motionless, and contemplates RODRIGO in silent stupefaction.]

RODRIGO: O my Carlos . . .

Aria 1, "Per me giunto è il dì supremo"

For me the ultimate day has dawned.

No, never more will we see each other;

may God reunite us in heaven,

He who rewards the faithful.

In your eyes I see tears --

weeping thus, why?

No, take heart, take heart;

The last breath is happy

of him who dies for you.

No, take heart, etc.

Recitative, "Che parli tu di morte?" -- and surprise!

DON CARLOS [trembling]: Why do you talk of death?

RODRIGO: Listen! Time grows short.

I have turned back onto me the terrible thunderbolt.

Today it's no longer you who are the rival of the king.

The bold agitator for Flanders -- it's I!

DON CARLOS: Who could possibly believe that?

RODRIGO: The proofs are tremendous!

Your papers found in my possession,

are clear testaments to rebellion,

and on this head for certain

a price has already been set!

[Two men are now seen descending the prison staircase: One of them is dressed in the garb of the Holy Office; the other is armed with an arquebus. They stop for a moment and point out to one another DON CARLOS and RODRIGO, by whom they are unseen.]

DON CARLOS: I will reveal everything to the King!

RODRIGO: No, save yourself for Flanders!

save yourself for the great work that you will have to accomplish.

A new golden age you will cause to be reborn;

you were meant to reign, and I to die for you!

[The bearer of the arquebus now takes aim at RODRIGO and fires.]

DON CARLOS [stupefied]: Heavens! Death! but for whom?

RODRIGO [mortally wounded]: For me!

The vengeance of the king couldn't be delayed!

[Falls into the arms of DON CARLOS]

DON CARLOS: Great God!

Reciative, "O Carlo, ascolta"

RODRIGO: Oh Carlos, listen! Your mother, at San Yust,

tomorrow will expect you -- she knows everything.

Ah! the ground gives way beneath me --

my Carlos, give me your hand --

Aria 2, "Io morrò, ma lieto in core"

I die, but light of heart,

since I have thus been able to preserve

for Spain a savior.

Ah! do not forget me!

Do not forget me!

You were meant to rule,

and I to die for you!

Ah! I die, but light of heart,

since I have thus been able to preserve

for Spain a savior.

Ah! do not forget me!

Ah! the ground gives way beneath me!

Ah! do not forget me!

Give me your hand . . . give me . . .

Carlos, farewell! Ah! ah!

[RODRIGO dies. CARLOS falls, in despair, on his body.]

["Per me giunto" at 3:35; "Che parli tu di morte?" at 6:34; "O Carlo, ascolta" at 8:31; "Io morrò" at 9:38] Tito Gobbi (b), Marquis of Posa; Mario Filippeschi (t), Don Carlos; Rome Opera Orchestra, Gabriele Santini, cond. EMI, recorded Oct. 5-14, 1954

["Per me giunto" at 2:45; "Che parli tu di morte?" at 5:23; "O Carlo, ascolta" at 6:55; "Io morrò" at 7:52] Ettore Bastianini (b), Marquis of Posa; Richard Tucker (t), Don Carlos; Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, Kurt Adler, cond. Live performance, Mar. 5, 1955

["Per me giunto" at 2:55; "Che parli tu di morte?" at 5:28; "O Carlo, ascolta" at 6:59; "Io morrò" at 7:59] Robert Merrill (b), Marquis of Posa; Giulio Gari (t), Don Carlos; Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, Fausto Cleva, cond. Live performance, Apr. 4, 1959

["Per me giunto" at 2:54; "Che parli tu di morte?" at 5:47; "O Carlo, ascolta" at 7:30; "Io morrò" at 8:28] Nicolae Herlea (b), Marquis of Posa; Franco Corelli (t), Don Carlos; Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, Kurt Adler, cond. Live performance, Mar. 7, 1964

["Per me giunto" at 3:06; "Che parli tu di morte?" at 5:34; "O Carlo, ascolta" at 7:15; "Io morrò" at 8:18] Mario Sereni (b), Marquis of Posa; Plácido Domingo (t), Don Carlos; Vienna State Opera Orchestra, Silvio Varviso, cond. Live performance, June 17, 1968

["Per me giunto" at 3:26; "Che parli tu di morte?" at 6:16; "O Carlo, ascolta" at 8:02; "Io morrò" at 9:09] Piero Cappuccilli (b), Marquis of Posa; José Carreras, Don Carlos; Berlin Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan, cond. EMI, recorded Nov. 15-20, 1978

Now, as to the Rodrigo of Tito Gobbi (1913-1984), a performance of which I didn't have especially fond memories, which I didn't even plan originally to include here. I think of this scene, from the baritone standpoint, as one that's built on, and at the same time shows off, the musico-dramatic potential of a prime Italian-style baritone, and however one may regard Gobbi, sheer vocal prowess wasn't something one turned to him for. Nevertheless, I decided to make the audio clip, and after making it listened to it casually, not having heard Gobbi's Prison Scene in I-don't-know-how-long, and was surprised by the simplicity, bordering on matter-of-factness with which he conducts so much of this final interchange with the character's dearest friend.

It's not only an unexpected choice for this particular singer but distinctly out of character for this particular character, whom the audience has met, before this point, in in a striking variety of situations, all of which he has handled with a particularized flair of widely assorted but unmistakably dramatic sorts: hearty old-comradeship, impassioned bosom-buddiness, consummate aristocratic ease and elegance, even dapperness, deeply held social conscience -- always alive to the situation and always "on," Verdi having crafted for each of the character's personae, frequently shifting on a dime, a musically and vocally dead-on "performance mode."

I have no idea whether it was an interpretive choice of Gobbi's to handle so much of a scene that the character himself might understandably think of as his "final performance" in such a relatively drama-free way. Of course back then, when the opera wasn't performed anywhere near as often as it has come to be, Gobbi may not have thought he was "deviating from the norm" for this scene. However it came about, the choice caught my attention, since this time through the Prison Scene I happened to be approaching it with a focus on this special knowledge of his sealed fate which Rodrigo is carrying around: the knowledge that he's about to die, with just one piece of business left to transact. It struck me as an interesting choice.

I'm not even saying it's necessarily a good choice --

The audience, after all, is as out of the loop as Carlos when Rodrigo makes his entrance, and so has no expectation to be contradicted. In addition, that final piece of business of Rodrigo's is important enough, and the time consideration perilous enough, as to suggest a perhaps heightened level of urgency, which we might note is certainly not suggested by conductor Gabriele Santini's extremely moderate pacing. I wonder too whether this was a dramatically motivated choice; Santini, after all, didn't need much of a nudge into slowpokedom.

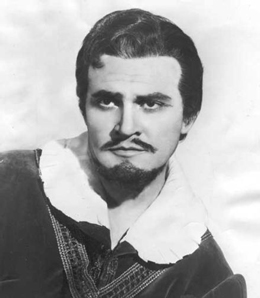

It occurs to me that on LP I know I have at least one other Gobbi Rodrigo, from Covent Garden, 1958, with Carlo Maria Giulini conducting. And of course Santini got to rerecord Don Carlos, for DG in 1961 (the first recording of it in five-act form), though I don't know whether these performances would tell us anything about what either Gobbi or Santini was thinking in 1954. Santini, for one thing, in 1961 had as his Rodrio the considerably fuller-throated Ettore Bastianini (at right, 1922-1967), sounding in fact a deal fuller-throated than he does in the 1955 Met performance we're hearing here. (The very idea of fuller-throatedness sounds a kind of uneasy note applied to a singer who would be diagnosed with throat cancer in November 1962, at age 40. For the record, Bastianini, after undergoing treatment, managed to sing a surprising amount in the years before his death, in January 1967.)

Come to think of it, we could also listen to Bastianini's Rodrigo with Herbert von Karajan from the 1960 Salzburg Festival, which for that matter might pair interestingly with the sampling we've heard from Karajan's 1978 Berlin studio recording, which is here for reasons other than my deep admiration.

As for our other Rodrigos, Robert Merrill (1917-2004) earned pride of place -- you'll recall that at the top of the post we heard him in both 1950 and 1959, in addition to this fuller version from the 1959 broadcast) partly because Rodgrigo is a role I think was especially well suited to the wide-ranging usability of his lovely baritone and partly because hearing him in this role, one he never got to record, evokes pleasant memories for me -- he was the fondly remembered Rodrigo of my first Don Carlos, at the Met a few years after the 1959 broadcast performance. The title role of that fall 1963 Don Carlos, by the way, was sung by Richard Tucker, who also made a fine impression. I've slipped him in here via the 1955 Met broadcast with Bastianini, where he sounds noticeably fresher than when I heard him. (We've heard excerpts from a 1952 broadcast where he sounds quite gorgeous.)

Mario Sereni (1928-2015) is another nostalgia pick for me. As I've mentioned probably more than once, we go back together to my very first Met performance, a weekday matinee for students of The Barber of Seville in March 1963 in which he sang the title role, and I've always loved the basic nappy timbre of the voice. You wouldn't think of him for the heavyweight Verdi roles: Germont, Ford, even Amonasro, fine; Rodrigo, not so much. But I've got this Vienna performance, and even with the measure of vocal shortfall, Sereni gives me a lot of pleasure. (One thing I don't have is so much as a note of his Figaro, which wasn't one of the fair number of roles he recorded -- and I'm not aware of a recital record on which he might have sung "Largo al factotum.")

Finally there's the case of Nicolae Herlea (1927-2014), whom I remember enjoying on several Met broadcasts during his brief company tenure (1964-66), though I never saw him live. The Met Archives has enthusiastic, practically glowing reviews by Peter G. Davis in Musical America for his debut-season Rodrigo and Tonio. Our Prison Scene excerpt, as it happens, is from his debut performance, of which P.G.D. wrote:

Mr. Herlea is a valuable addition to the company, for he possesses a large but well-focused velvet-hued voice that responds beautifully to all his wishes. Starting out somewhat hesitantly with a pronounced tremolo, Mr. Herlea gathered strength as the opera progressed, and sang his two arias in Act III with a sumptuous Verdian line.I think we can confirm that "sumptuous Verdian line"! Of the Pagliacci P.G.D. wrote:

Nicolae Herlea proved to be an outstanding Tonio in all respects. I have not heard the "Prologue" bettered since Leonard Warren's days, and the baritone also displayed some very positive dramatic qualities.Subsequently at the Met Herlea sang Rigoletto, Lucia di Lammermoor's brother Enrico, Don Carlo in Forza, Rossini's Figaro, and even a couple of tour performances of Valentin in Faust. Reviews of the later performances are less enthusiastic, and Met supremo Rudolf Bing seems to have felt himself well enough stocked with Verdi baritones as to have no further need of our Nicolae's services.

Happily, back home in Bucharest Herlea recorded such roles Figaro, Rigoletto, Don Carlo, and Tonio (YouTube samples include the complete Pagliacci Prologue, which readily confirms what P.G.D. heard in New York). In all of the above he's much the most interesting performer. However, he did record Germont opposite his countrywoman Virginia Zeani, who gave us one of the most persuasive Violettas on record. (Ion Buzea isn't in their class but holds his own as Alfredo.) We've already heard Zeani and Herlea do the great Act II scene, but there's no reason we can't hear it again. And while we're at it, I thought that for the benefit of Mario Sereni fans everywhere, we'd rehear another performance of the scene with our guy and a soprano you may have heard of -- not for comparison but to complement, an impromptu tribute, I think, to the scene's greatness, that such powerful truths can be found in it in such different ways.

VERDI: La Traviata: Act II, Scene 1: Violetta-Germont scene

[You can find quite usable English-Italian Traviata texts here.]

Virginia Zeani (s), Violetta Valéry; Nicolae Herlea (b), Giorgio Germont; Orchestra of the Romanian National Opera (Bucharest), Jean Bobescu, cond. Electrecord-Vox, recorded 1968

Maria Callas (s), Violetta Valéry; Mario Sereni (b), Giorgio Germont; Orquestra Sinfonica Nacional, Franco Ghione, cond. Live performance from the Teatro São Carlos, Lisbon, Mar. 27, 1958

ONE FINAL NOTE ABOUT THE DON CARLOS SCENE

Oh yes, you may have wondered what the Cappuccilli-Carreras-Karajan performance is doing here. One answer is: not much. Not doing much at all. More to the point, now that I've incorporated into this post a short version of my horrifying encounter with Karajan's 1986 Salzburg Easter Festival video Don Carlos, you may guess that this has something to do with that, and it does.

I've never listened much to the Karajan-EMI Don Carlos. A quick first hearing told me as much as I needed to know. Nervertheless, I didn't remember being this put off by it. Still, proceeding on the assumption that it would be useful in trying to write about my shock confronting the video performance, I went ahead and made an audio clip. Then, while trying to make progress with a hypothetical blogpost, I listened to the clip and was startled to find it kind of, well, OK. Certainly not great, but not the D.O.A. wreck of the video.

Then I realized that the audio recording didn't date from the year before the video, as I casually assumed, since in those decades, going back to Karajan's awfully good and genuinely important DG Ring cycle, his general practice had been to schedule a studio recording of an opera the year before he planned to do a stage production, so that everyone involved in the stage production could use the recording for preparation and eventually rehearsal. Now, he may well have done this with Don Carlos, but I'm assuming that the 1986 Salzburg Easter performances were a revival rather than a new production, because the audio recording was made significantly earlier, in 1978. And those eight years made a huge difference to the two principals who sang in both. In 1978 Carreras's voice was less distressed and Cappuccilli's still commanded enough singing tone to make possible the production of sung phrases. The Berlin Phil still seems to me a dead zone, if not as cripplingly so as in, say, Karajan's EMI Trovatore and Otello. And I have to say, I don't hear much conductorial feel for the piece, with which Karajan did have a history, in the 1978 recording.

But hey, you may like what you hear here, and if you do, you probably won't have a hard time tracking down a copy.

THE 2021 "INAUGURAL EDITION"

(SUCH AS IT IS, SO FAR)

No. 1: "Wanna hear in full the marches we heard in part during today's (pitch-perfect, I thought) inauguration?" [1/20]

No. 2: "Post tease: Sarastro sings a mouthful when he sings, 'The rays of the sun drive away the night'" [1/24]

No. 3: "While I toil away at this week's Inaugural-themed post, let's hear the end of The Magic Flute in our five performances -- plus a couple of 'new' ones" [1/27]

No. 4: "It's not just Sarastro who sings to us about the miraculous restorative powers of the sun's rays" [1/29]

No. 5: "Post tease: Has any operatic act begun more beautifully? (Not to mention suggestively?)" [1/31]

No. 6: "Inaugural Edition, no. 6: For now, no explanations, just music (that's the theory, anyways): Two operatic chunks, by Debussy and Verdi, that have lodged in my head" [2/16]

#

No comments:

Post a Comment